Pro Hart Artist– Aussie Legend and people’s painter

Once in awhile, an artist comes along and delivers to the people, not just a painting, but a story, a personality, and a real quality and sense, of what it is to be a true Australian. Pro Hart inspired Australia through his creative, and somewhat unorthodox methods of painting and sculpting; he gave us a laugh, and made us look at the world with humour in our hearts. This essay will discuss the historical and social context of his life, paintings, beliefs and values. It will shed light on his innovative scientific advancements in authenticating his works, how his childhood shaped his interest for art. How he passed his artistic knowledge onto a new generation of artists, and will consider how the “art elite”, treated and alienated both him and his work. It will also address the way he got involved in social and political issues.

On a cold night in 1928, Kevin Charles Hart was born near the New South Wales town of Broken Hill. (Hart, 2007, 11). A mining town renown for it poor living conditions, and dust storms in its earlier days, expanded to supporting over 21,000 people after infrastructure like schools, a post office, town hall, jail and the development of the towns water supply were built in 1951.

In his earlier years Hart lived on a sheep station owned by his grandfather Arthur Hart. He was home schooled by correspondence, something his mother was very strict about. He found school difficult and unable to express himself in words, he would illustrate stories instead of writing them, something his teacher encouraged. His love of drawing would fill most of his spare time; he even put together a comic book depicting people he knew. It was passed around by neighbouring kids, who enjoyed the entertaining drawings. Hart referred to living at Larloona Station, as being a very boring time in his life. (Hart, 2007, 13-16)

In 1941 Harts father moved the family to Broken Hill, he believed firmly in educating his children, enrolling them at Marist Brothers Catholic College. Hart went on to achieve an eighth grade education before starting his first job as a bakery delivery driver, delivering bread on a horse and cart. Twelve months later he left the job after contracting peritonitis, which almost took his life. According to Hart, he started working at 19 years old in the mines, which seemed like a rite of passage in those days, if you were born and raised in Broken Hill. During his time underground Hart would for fill his growing interest in art, by painting on his breaks on the lunch room walls, on lifts, doors and anything else he could find to paint on. (Hart, 2007, 17-18).

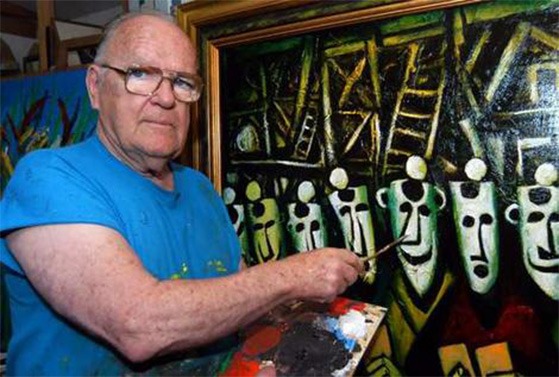

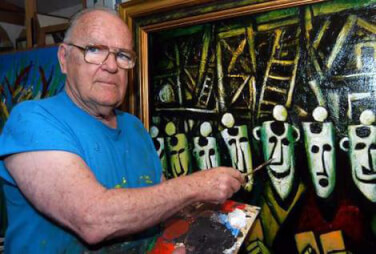

Hart had a larrikin style of painting, and a style that did not mesh with the traditional and historical styles and influences of painting at the time, and some would suggest an unorthodox way of painting. He was known to shoot paint straight out of a canon, and bomb paint out of balloons or drop it from a plane, in an attempt to experiment with paint, and the general novelty of the process. Pro Hart Artist, explored numerous artistic avenues venturing into etchings, silk screening and turning his hand to sculpture. He often blew up sheet metal with dynamite, before shooting it with a machine gun, and welding it together (Sysum, n.d)(Hart, 2007, 62). According to son David Hart, the most interesting sculpture his father produced, was an ephemeral one to launch an exhibition at the Elderfine art gallery in Adelaide. Hart froze champagne bottles inside 100 pound ice blocks, and then placed steel welded flowers on top. The concept was that people had to guess how long it would take for the ice to melt, and as they melted the champagne was available for the public consumption (Hart, 2007, 62)

Hart refused to be a conformist, too him it was about the finished painting, and not what it was painted on. He painted murals on cars and car bonnets, refrigerators, underground in crib tins, on t-shirts, beer kegs, police cars, motorbikes, aircrafts, pipe organs, and even on an excavator all in the name of charity (Hart,2007, 63).

Hart had an infinite fascination for mechanics, often producing interesting gadgets and inventions such as a baby pram rocker, which he devised from a car windscreen wiper motor, and odd scraps of steel. He gained a reputation by his mining mates for always inventing something, and as a result they referred to him as the “Mad Professor”. The name proved a little tedious to say all the time, so it was shortened to “Pro,” a name that indelibly stuck with him for the rest of his life. Hart disliked the constant infatuation with how he was awarded the nick name, and hated even more having to repeat the story when asked. He went so far as to avoid opening nights or interviews, because he knew that the same old question would be raised time and time again, and according to his son David Hart, he truly dreaded the question. (Hart, 2007, 11-12).

Hart married Rayleee Tonkin 11 years his junior in 1960, and had five children, all who have followed their famous father’s footsteps into the art world. Although Hart publically said that you cannot teach someone to paint, you can only teach technique, it was something he always made available to his children. He would set up paper, brushes and paint, and whenever they would go to him, he would direct them to the paper to discover paint for themselves. Hart was then able to show receptive children his technique, which has allowed them the freedom to become individual artists in their own right. (Hart, 2007, 105-106).

David Hart the youngest child is a well known artist, author, businessman, and entrepreneur and owner operates 2 successful art galleries on Queensland’s Sunshine Coast. His work is collected by Presidents, Prime Ministers and Hollywoods elite movie stars, and continually keeps his father’s paintings and legacy alive and well in his galleries (Hart, 2007, 283). Harts daughter Marie Hart has a successful gallery and art school in Broken Hill, called The Red Chair Atelier. She has exhibited her work since 1983. In a mixed exhibition at the Adelaide Casino in 1997, she out sold her father, and since then her work has sold all over the world. Her work whilst extremely distinctive from her father’s, attributes him as her greatest influence (Mary Hart, n.d).

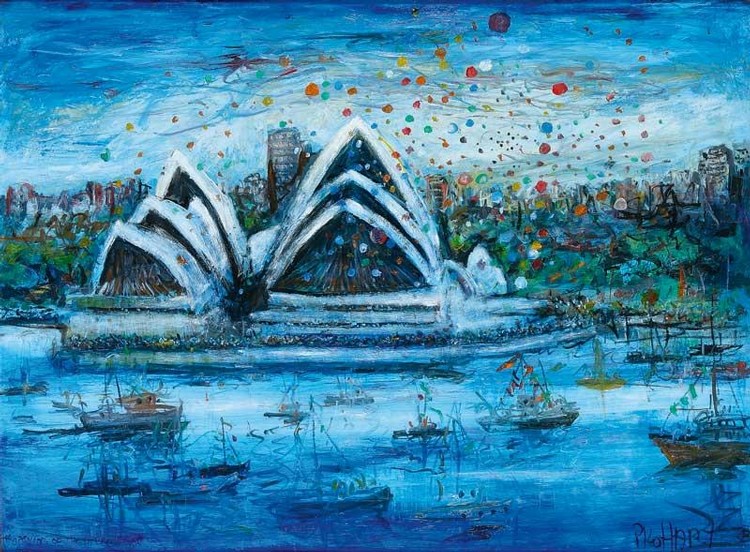

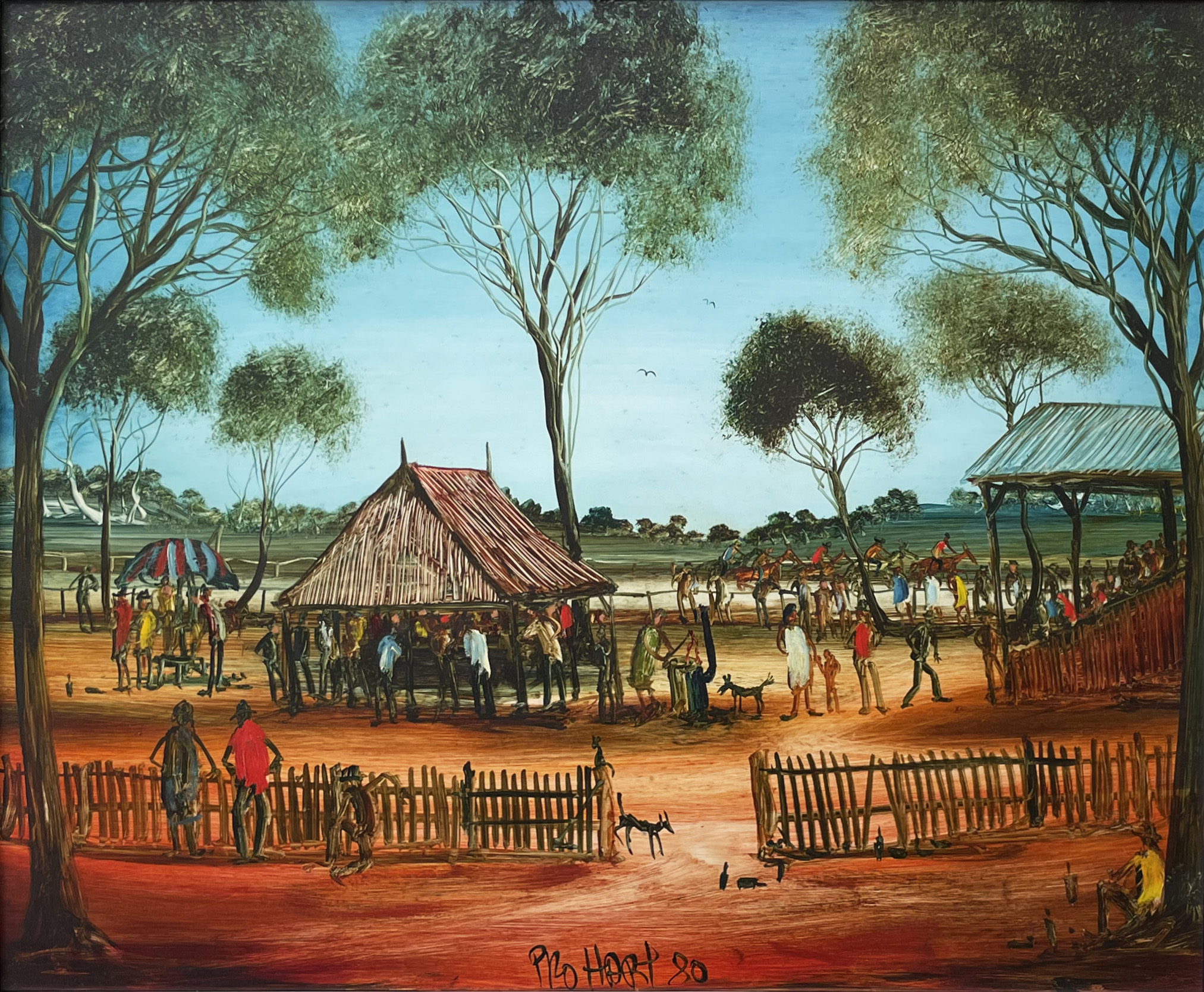

Hart started full time painting in 1958, where he painted everything from miners at work, landscapes, religious depictions, political scenes to everyday scenarios such as mates at a pub (Pro Hart, n.d). He discovered early on that he could draw from people’s own experiences, using the tales they told and laughed about at the local pub and incorporating that humour into his historical and present accounts of daily work and play (Hart, 2007, 46). Works such as “Wives revolt during the Broken Hill strike, 1975, which depicts women by a puddle of water with a naked mans clothing, is a portrayal of the women of Broken Hill struggling for equality and rights.”Mining town Sunday” 1975, shows a town of people doing childish activities, like riding in a wheel barrow and falling off a bike. Both paintings were painted in 1975, but depict different levels of humour and social repercussion, whilst still maintaining a level of narration and a sense of knowing exactly what is happening within the work (Lumbers, 1977, 93, 109).

In 2002 the legendary Pro Hart Artist started an historical authentication process for his art, which included a comprehensive combination of his DNA. When combined with an invisible optical indicator, it formed a complex DNA matrix, which was then delicately applied to Harts paintings. The combination of ingredients makes it near impossible to copy, and allows for an electronic verification that each work is indeed a Pro Hart original. A digital image is completed including the work details, and the DNA location on individual paintings. The microchip details are logged into a computer data base, allowing investigators to confirm authenticity from anywhere in the world. This was done to try and combat the number of alleged counterfeits offered for sale and to protect consumers from buying a forgery (Pro Hart, n.d). Whilst Hart was not the first artist to ever use DNA on a painting, he was the first artist in the world to use it for the sole purpose of authenticating his original works (Etching house, n.d). Danish born artist Uwe Max Jensen consistently uses urine, blood and excrement in his works, however it is not for the purpose of identification, rather than to achieve controversy and push the boundaries of conceptual art, he believes people only like paint on canvas, and why, when everyone has a natural pallet inside their bodies for free (Channel 9 news, 2006).

Hart did not have an easy road to fame and fortune, after his first exhibition that was held at the Kim Bonythan Gallery in 1962, his popularity grew steadily, however it was by regular people that he was most embraced (Hart, 2007, 33). T he conservative “art establishment” which included reviewers, curators and major galleries all refused him the respect others in the art community felt he should have received (Sydney Morning Herald, 2006). Margaret Carnegie, who was well respected in the art world said those in the Australian art scene had favourites, and Pro Hart was not one of those. Critics have been murderous about his works from the beginning (Lumbers, 1977, 31). Hart was called many names over his career, such as a “repetitious folk artist who had no purpose”, and an artist with “no academic substance”. Hart didn’t worry about what critics had to say, saying that they would never succeed in stereotyping him into history, purely because he wasn’t like any other artist of his time, or historically speaking (Hart, 2007, 94). This comment may have been true; however it did not stop critics comparing his work to other past or present artists. Elwyn Lynn believed in Harts work, defining it as “a real artist trying to break out”, he enjoyed the positiveness of his paintings, and believed Australian critics didn’t like his work because it was too bright and polished, and they were more accustomed to a softer pallet of other artists in history and artists currently available at the time. Hart was too far from how they believed a painting should look. He was a painter of the people, and not a painter’s painter, and this simply did not gel with critics who believed his work was repetitious, and that painting beyond the witchetty grubs was simply out of his league (Lumbers, 1977, 32-33). One comment cut very deep and Hart was very hurt. His son John Hart recounted that his father mentioned his feelings about Robert Hughes’s comments, describing Hart as “Parish pump incompetence”, as a comment that stuck with Hart till the end.

Pro Hart paintings were never acquired by the National Gallery of Australia, or the Art Gallery of New South Wales, which was Harts home state. Ironically the one painting each gallery has, was sent to them as a gift by Hart. “At the trots” was only hung after Hart’s death from motor neurone disease in 2006, as a mark of respect and due to growing public pressure, until then it had spent 30 years in storage. But even then Barry Pearce, the Australian art gallery curator at the time, and one of very few who were willing to go on record about the lack of industry support for Pro Harts work, still failed to give Hart the credit the public felt he deserved. Pearce’s degrading comment suggested that “By comparing Hart with the artists who normally hung in the gallery, is rather like Slim Dusty being compared to Mozart” (Sydney Morning Herald, 2006).

The very talented Pro Hart Artist had strong beliefs which came across in the art, he enjoyed exaggerating the everyday mundane, spicing it up, he loved to watch people, especially at events where they were relaxed and having fun such as the races. He was an opinionated man and had radical ideas, when asked about his politically influenced paintings, he would say it is better to paint what l think, then to get sued for saying it. He liked to bring what he thought to the court of public opinion and let them judge it for themselves.

In this essay l have talked about how Harts earlier years growing up, how he received his nick name of “Pro”, his influence on his artist children, how he was socially and professionally ostracized by the “Art elite” including major galleries, and scorned by art critics. His social conscience and beliefs were looked at, such as his reaction to the Lindy Chamberlain’s trial in 1980, and how he placed his weight behind her struggle for freedom. Harts innovative and historical introduction of DNA to authenticate his works was revealed and how Hart strives to give back to the community through his charity paintings. Long live an Aussie legend.